Digital border apps in Americas could misuse asylum seeker data

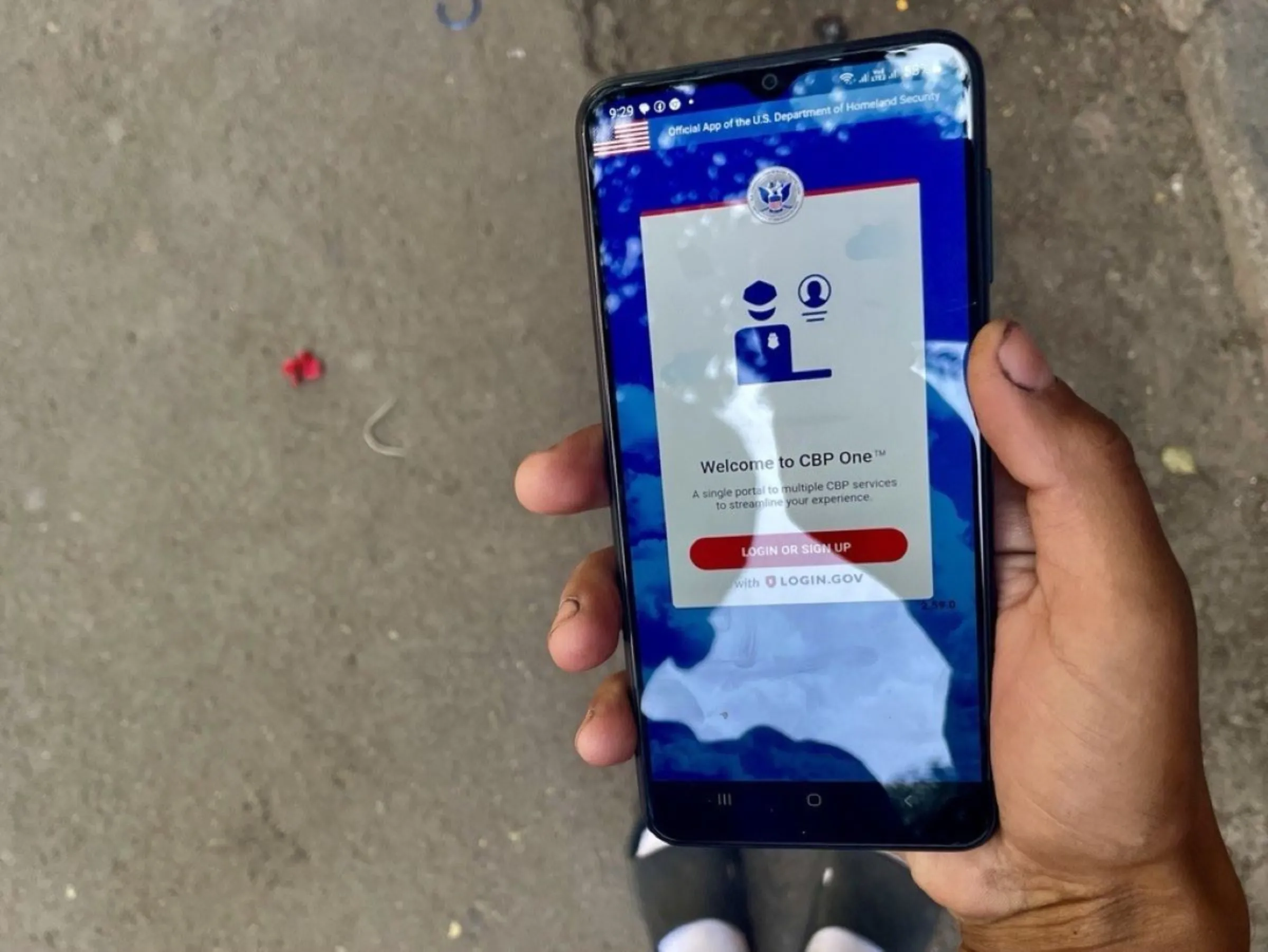

A migrant seeking asylum in the U.S. uses his phone to access the CBP One App in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, January 12, 2023. REUTERS/Jose Luis Gonzalez

What’s the context?

New research says phone apps launched to regulate migrants and asylum seekers in Americas may violate digital rights

- New research warns of digital rights violations

- CBP One app used at US border garners criticism

- Colombian app may not protect data, advocates say

MEXICO CITY/BOGOTA - Sitting next to dozens of worn, multicoloured tents on a street in downtown Mexico City, two Venezuelan siblings wait for the clock to strike 10am to take out their phones and apply for an asylum appointment in the United States.

Like others in the migrant camp, they are obliged to use the CBP One app to schedule an appointment to present an asylum claim with the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) at the U.S.-Mexico border.

"We don't really know what they do with our information. But this is our only option to enter the country legally," said Alessandra Castillo, 39, who has been waiting for 15 days to get an appointment for her and her brother through the app.

Since 2023, tens of thousands of migrants and asylum seekers travelling overland across South America towards the U.S.-Mexico border have had to use mobile apps to register their travel, or schedule appointments with migration officials.

But advocates worry the new 'digital border' violates migrants' and asylum seekers' digital rights, with governments playing fast and loose with their sensitive data and increasing the surveillance of vulnerable communities.

"When you register yourself in the app, there's a privacy (notice) you have to accept to be able to continue," Mary Kapron, researcher at rights group Amnesty International, told Context.

"And many asylum seekers don't understand what it means but accept it anyway, because that's the only way to continue on with your registration."

This week Amnesty International released a report saying the CBP One app failed to provide information on whether asylum seekers' photographs, which are uploaded onto the app, are being shared with other government agencies.

The report also said the app's facial recognition functionality could lead to mass surveillance and discrimination against asylum seekers of certain races, ethnicities and national origins.

Since January 2023, more than 547,000 people have booked an appointment through the app, according to the CBP's most recent data.

Aside from the digital rights' concerns, people like the Castillo siblings face other challenges in using the app, which only grants 1,450 appointments per day, forcing asylum seekers to register daily until they are allocated a slot.

This means the siblings spend ages scrolling through social media looking for tips on how to successfully score an appointment.

To do this, they have to rely on the city's intermittent public WiFi network, make sure their phones are charged and navigate the online scams and disinformation that have sprouted up around the CBP One app.

Venezuelan asylum seeker, Alessandra Castillo, shows the CBP One app on her phone at a migrant camp in Mexico City, Mexico, April 29, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Diana Baptista

Venezuelan asylum seeker, Alessandra Castillo, shows the CBP One app on her phone at a migrant camp in Mexico City, Mexico, April 29, 2024. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Diana Baptista

"We can charge our cellphone at a parking lot, but they (the owners) charge us – everything has a cost here," said Luis Castillo, 25, whose dream is to get a job in New York.

These challenges are highlighted in another report, published by Human Rights Watch in May. It found that the app which only operates in English, Spanish and Haitian Creole, also excluded asylum seekers based on "their race, digital literacy, ability to read or write, language, age or disability".

The report said some asylum seekers might not have cellphones - either because they could not afford one or had been robbed - while some devices might not have enough memory space to support the app.

"States are able to use technology in a way to make migration and asylum procedures more efficient, but they shouldn't become a barrier to the ability of people to seek asylum," Amnesty's Kapron said.

In a privacy impact assessment from 2021, CBP said the app had a privacy notice requiring the consent of users and that it had mitigated the risk of surveillance by not tracking the users' movements.

Safe transit

Concerns about whether mobile apps meant to regulate migration might be violating users' digital rights have also reached South America, where government data shows 80,000 migrants have registered so far with the Tránsito Seguro (Safe Transit) app launched last year by Colombian authorities.

The app requires migrants from 30 nationalities, including citizens of Haiti, Cuba, Bangladesh, China and Venezuela, to register their journeys and provide personal data to allow them to transit through Colombia for 10 days without a permit.

For many migrants this means traversing the Darién Gap - a treacherous stretch of rainforest straddling Colombia and Panama - as they make their way north to the United States.

Migrants heading to the U.S. wait at the Migrants Reception Station in the Darien province, Panama, September 23, 2023. REUTERS/Aris Martinez

Migrants heading to the U.S. wait at the Migrants Reception Station in the Darien province, Panama, September 23, 2023. REUTERS/Aris Martinez

According to the Colombian government, the aim of the 'Safe Transit' app, available in Spanish, French, English and Portuguese, is to help tackle human trafficking and smuggling of migrants.

A government document outlining the terms of use of the app states that personal data collected could be transferred to other authorities in or outside of Colombia with "the aim of processing information to guarantee orderly and safe migration."

It also said migrants have rights relating to the "protection or processing of personal data".

But digital rights campaigners say the app lacks basic data protection guarantees, and most migrants do not know if and how their personal data will be shared, how long it will be stored, and what it will be used for.

"It is worrying that the app has no data privacy guarantees. Vulnerable migrants are being asked to upload a photo of their face and information about their children," said Lucía Camacho, public policy coordinator in Colombia with Derechos Digitales (Digital Rights), an advocacy group based in Chile.

"The Colombian government is failing to provide the minimum guarantee of data privacy. Data on the app isn't encrypted and so isn't safe," she said.

Comments left on Facebook groups for migrants seeking to cross the Darién Gap show that the use and purpose of the app is confusing - with many deciding not to use it at all.

As many migrants who cross through the Darien Gap do so illegally and often without the proper paperwork, most will not download the app and will not be questioned by migration officials, who are not present at many border jungle crossings.

Alejandra Rojas, a Venezuelan migrant and mother of two young children who moved to Colombia five years ago and is planning to join relatives already living in the United States, said she did not know about the Tránsito Seguro app.

"I don't have a passport and my identity card is out of date so I wouldn't have the information to upload on the app. I wouldn't use it anyway," said Rojas.

(Reporting by Diana Baptista and Anastasia Moloney; Editing by Jon Hemming and Clar Ni Chonghaile)

Context is powered by the Thomson Reuters Foundation Newsroom.

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles

Tags

- Disinformation and misinformation

- Digital IDs

- Tech and inequality

- Data rights